8 Thoughts from 2018

2018 has come to an end and it’s always great to look back and reflect. In this post, I’ll try to summarise some of the thoughts, adventures, experiments, and new ideas I’ve been dabbling with.

Minimalism

It seems like minimalism is yet another trend that is being heavily popularised. It’s everywhere in pop culture. It’s manifested in party flyers, fashion, beer labels, industrial design, the interior design of cafes, and web design. In other words, cafes are beginning to become indistinguishable from an apple store.

The good news is that minimalism is now consumable (⸮)

Looks schmick, doesn’t it?

Bier beer has done a remarkable job on that front. It appears to send an authentic and respectable message, however, it is still nested within a consumer-oriented approach. I mean, it’s not merely about the qualities of the beverage. It’s ultimately about the story its consumers want to tell their social environment about their personality as an individual with certain aesthetic preferences and the consequences this has on their social status.

NO BLAH BLAH

Our products have neither a name, nor a logo. Behind them stands a simple message: to never promise more than we can deliver; forgoing all marketing blah-blahbery and showing a middle finger to the visual pollution humanity is relentlessly subjected to via product advertising and branding.

No name. Just taste. Because it’s what’s inside that really counts.

(Bier Bier)

All things considered, minimalism is a positive change given the complex world we live in. Have you tried operating a smart TV recently? a microwave? Why are these devices so difficult to use?

It’s easy to see why we yearn for simplicity.

Like many trends, they’re often rooted in a truth that is exaggerated.

Simplification is a constant process of streamlining things in my life. I still remember the freeing effect of giving away all my valuables when I started a meditation retreat a couple of years back. Not having to worry about phone, wallet, and keys is a reminder that we’ve survived most of human history without those things.

Digital Nomadism

January in Berlin is most signified by the harsh ceaselessly grey winter and the anticlimax of the post-holiday season. Winter escapes are an effective means of combating the psychological consequences of the dark leafless period.

In 2018, I tried something a little different. Instead of travelling, I wanted to spend time living abroad in a purposeful manner. I had already read much about digital nomadism and I was excited to have another project to research.

A digital nomad is simply someone who can live and work from any location given a job in the cyberspace. In reality, it’s often millennials who’ve read too many self-help books and belong to a demographic referred to as WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, And Democratic).

I used Nomad List to find a befitting location — Chiang Mai Thailand. Nostalgia was one of the reasons, given that I’d visited Chiang Mai in 2008. Granted, the city was going to be very different after 10 years, but so was I.

I spent a little over a month in Chiang Mai in an up and coming trendy area called Nimman. I’ve developed a slight distaste for the herd mentality of such trendy areas in different cities. They commonly repackage consumerism with a more palatable wrapping for millennials. That includes minimalist cafes, locally roasted coffee, avocado in everything restaurants, a variety of vegan options, and an excessive amount of selfie sticks everywhere you turn your head.

Having said that, I was content with the apartment I found, the hustle bustle of the area, and the late night food stands. I devised a routine that would allow me to get some focused work in the morning before my colleagues start in Berlin, exercise, socialise, and read. A good friend from Berlin was also visiting Thailand for the first time which made the experience yet cosier. My parents also came to visit me and we had an amazing time together.

I had a serendipitous encounter on one of my first days when I met a fascinating grizzled Englishman named Dave. Dave is a treasure chest of life experience and adventure stories. All a product of vivid eventful life. We became friends very quickly and started hanging out. Until today, I reflect on our conversations and the impact he’s had on my world view. A passionate contrarian he is.

Millennials

Millennial is an ambiguous word. Generally, it refers to the demographic born between the early 1980s until mid-1990s. I think the extreme individualism and lust for instant gratification is a regression to individual and collective well-being, which manifests as depression and loneliness. Some say it’s irrelevant to talk about generational changes as regression and I agree to a certain extent. But every generation also has a counter-culture and being a critical thinker means challenging the status quo.

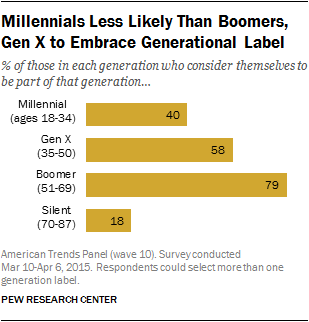

So individualistic we don’t even identify with our label

Individualism & Consumerism

I believe that millennials have benefitted from unprecedented freedom that has given rise to individualism that, while generally positive, coincided with a decline in our ability to collectivise. The documentarian Adam Curtis explores this idea in The Century of the Self, in which he draws the link between Freud’s theories and the rise of modern consumerism with individualism being the main vehicle to drive that change.

“To many in both politics and business, the triumph of the self is the ultimate expression of democracy, where power has finally moved to the people. Certainly the people may feel they are in charge, but are they really? The Century of the Self tells the untold and sometimes controversial story of the growth of the mass-consumer society in Britain and the United States. How was the all-consuming self created, by whom, and in whose interests?” (BBC Four)

Instant Gratification

Amazon Prime same day deliveries, Netflix, and the ability to reach millions of people with social media. We want everything now. But how well equipped is the human mind to handle this change? The most rewarding things in life seem to be challenging and require time. Working hard at a goal can be a truly uplifting experience.

I might be conflating different problems, but I think all of these technological trends play with our reward centres by giving us the feeling that we can get everything now. Towards the end of 2018, I deleted Facebook and Instagram from my phone and it’s been a welcome change.

The attention economy

Human attention is a scarce resource and increasingly valuable. Google, Facebook, and Amazon have become data companies. Most of the value they provide is data-driven. They collect enormous amounts of data, process it, and give it back to us in the form of digital goods and services.

Many concerns arise about the way these companies are developing and the role they play in the global community. I find that the most pressing concern is the way they affect human relationships. It’s becoming increasingly hard to just be bored. We’re bombarded with notifications that tap deep into our social and stimulation hungry minds.

Have you ever had the feeling that you’re having a conversation with someone and a ringing sound or vibration just dissolve the fragile thread of thought?

Do you remember that moment at a dinner party when everyone went quiet and all faces were illuminated by a smartphone screen?

Certainly, this is the price of convenience, and the benefits of connectivity cannot be understated. But I feel like we’ve truly lost something. I’ll run the risk of sounding like a romantic and say we’ve got all the connectivity in the world, but we’re forgetting how to connect to one another.

This is a constant struggle, for I want to enjoy both worlds. But sometimes one has to make a choice. If only one dinner party at a time.

Mindfulness might be one of the only effective cures to that.

Mindfulness Meditation

Our minds play a huge role in our lives. Every activity we do is experienced in the space of our consciousness. For a long time, this was an obvious axiom that I didn’t spend much time thinking about.

I vividly remember discovering that our sense of taste can only sense about 5 flavours — sweet, salty, sour, bitter and umami (savoury). This came as a surprise because I assumed that we can taste many more. But it turns out that when eating, our sense of smell complements the taste buds in creating the pleasurable eating experience. In fact, our sense of smell is capable of a much broader spectrum of sensations.

The epiphany didn’t get real until I did an experiment. I took a bunch of different flavoured jelly beans, blocked my nostrils, closed my eyes, and began tasting them. I was astonished to discover that I couldn’t tell them apart.

It struck me over time, that there’s an important distinction to be made between experiential and intellectual insight. Initially, I had an intellectual insight. But it didn’t register until I had the experience with the jelly beans.

Mindfulness meditation is a practice capable of conjuring experiential insight into the nature of our minds. The most important of which is the transient nature of emotions and sensations. Everything is constantly changing. For example, even anger is a series of different sensations that are each unique, and very often it is our aversion to is that prolongs it. This is something that can be observed in practice.

Meditation is like mental training. It’s fairly accepted today that physical training can increase stamina and strength. I believe that our minds are just as trainable as our bodies. I dedicate 10 minutes a day to meditation. Usually, I do it immediately after waking up. And it’s amazing how so little time can have such a subtle yet noticeable impact on everything in my life.

It’s worth mentioning that the change is very subtle. That’s why doing a retreat is highly recommended. A 10-day retreat creates an ideal environment for learning the practice while eliminating all distractions. Moreover, it’s a long enough period to reach a level that is otherwise difficult to bootstrap.

Books

Enriching my inner world of ideas underlies many of my endeavours, both consciously and subconsciously. Hence all the non-fiction. All books I’ve listed here have changed the way I look at the world. I really enjoy fiction, but I find that films are a preferable medium for fictional narratives.

- Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker.

- 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos by Jordan Peterson. I wrote a review of the book

- How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence by Michael Pollan.

- The Strange Order of Things: Life, Feeling, and the Making of Cultures

by António R. Damásio - The Square and the Tower: Networks and Power, from the Freemasons to Facebook by Niall Ferguson

- Can We Avoid Another Financial Crisis? by Steve Keen

- Mastering Ethereum: Building Smart Contracts and Dapps by Andreas Antonopoulos

- 21 lessons for the 21st century by Yuval Noah Harari

- The Dip by Seth Godin

- The Strange Death of Europe by Douglas Murray

I’ve skipped a bunch of chapters in The Square and the Tower. This is something I’ve learned to do. As much as I like thoroughly reading a book cover to cover, if I’m reading non-fiction and I’m not getting much from reading, I’ll either skip the chapter or stop reading. This was the case with The Strange Death of Europe that was simply too bleak to prioritise over other topics I’m more curious about.

Interestingly, I find that as I read more non-fiction, I become interested in the authors’ other creative outlets. And indeed, many of the authors listed here are ones I’ve come across as guests on The Waking Up podcast.

Decentralisation

Technological and political decentralisation is a topic close to my heart. I’ve written about it extensively following my resignation from a golden cage job I left.

My argument is that a growing family of open source technologies allow us to decouple money and value from governments thereby granting by their sheer existence individual sovereignty. They come with their own set of problems, namely that they’re still complex and awfully misunderstood. But they offer a glimpse into the future to come.

The community is leaderless rendering it fundamentally different to the traditional hierarchical structure of a corporation. There’s no Elon Musk that drives Tesla stockholders and NASA mad over smoking a joint — a legal act in California, where it took place — on a live Youtube stream. There are thousands of engineers developing many of these technologies every day globally. It’s exciting yet overwhelming.

In this talk, Andreas Antonopoulos, a bitcoin and decentralisation advocate, gives a thought-provoking talk about the confusion and instinctive disbelief from newcomers about how open, decentralised cryptocurrencies can scale and grow in value without the finality of approval from traditional authorities.

Scuttlebutt

Another fun project I’m following and using is called Scuttlebutt. Scuttlebutt is a peer to peer decentralised social network. Here's a talk I gave at a meetup in Berlin in which I explain what Scuttlebutt is and its technical underpinnings.

Truth-Seeking and Values

Given the current state of journalism and political polarisation, it has become difficult in casual conversations to make a clear distinction between the normative and descriptive claims.

In short, normative claims make value judgments, whereas descriptive claims are ones that describe reality.

For example:

- Descriptive claim: My beer is warm.

- Normative claim: Pilsner beer ought to be drunk cold.

As someone who values objective truth, learning both these terms and understanding the distinction has been a welcomed tool in conversation. Especially sensitive conversations where one can sense there might be a strong difference of opinion.

The philosopher David Hume described the Is-ought problem, in which he claimed that it is not obvious how to coherently move from descriptive claims to normative claims.

Science, for example, focuses on answering descriptive questions. But there are some moral philosophers, most notably Sam Harris, who argues that science can indeed answer moral questions, i.e. normative questions. In other words, science can determine human values. This is the main argument in Harris’s book The Moral Landscape.

So why do I bring all of this up? Those who know me, know I can have strong feelings about things. I do however make an effort to engage in intellectually honest conversations. A commitment to facts forms a foundation for making different normative claims. And yet, speaking about facts can feel burdensome.

A study of the neuroscience of disgust has shown that moral disagreement triggers the same parts of the brain responsible for the feeling of disgust. So it’s no wonder it’s difficult to have these conversations. At the same time, dialogue is the only effective error correction mechanism we have. Otherwise, it’s violence.

Life as an experiment

Our life consists of the choices we make. And yet, so many of the choices I feel we have on offer are a product of society’s social norms. I like to challenge the norms in a constructive way. So I treat life as an experiment. Because the alternative feels like the Choose Life monologue from Trainspotting.

Choose Life starts off as a parody of mainstream culture, defined by its superficiality and emptiness. It gets really sad when the monologue turns into an honest reflection of regrets from an unfulfilled life.

For all I know, we have only one go. And even if I’m wrong, why not treat it that way?

Freeing myself from the social norms and societal expectations and embracing unconventionality hasn’t always worked out, but I was often lucky enough to find myself engaged in creative endeavours surrounded by loving and supporting friends and family. This is by no means universal advice. It’s purely anecdotal based on my preferences which notably include autonomy and freedom.

2018 was a memorable year and 2019 will build on the same foundations, bringing much optimism in the midst of all challenges. I’ll be continuing to choose life, but perhaps a more deliberate and creative version of it.