Why does decentralisation matter?

I’ve decided to quit my job in the financial technology industry and to focus on decentralised technologies. This is a decision that has culminated over the last year or so. It began with the discovery of the technical principles behind Bitcoin and resulted in many new friendships, ideas, and interests. I plan on getting more involved in this exciting and thriving space.

This essay is an effort to organise my thoughts on how I currently see things. Much of the ideas I’ll explore are based on what I’ve read and listened to in the past two years. My background is primarily as a software engineer with experience in frontend development (user facing interfaces), backend development (the systems that the frontend interacts with to make software work), and most recently in infrastructure (the underlying hardware and software to allow everything to work together) and distributed systems (a field in computer science that focuses on building software that divides the workloads across different computers).

Prior to resigning, I was reflecting on my professional trajectory in the last eight years and to my surprise, I realised that most of what I developed did not have a significant and meaningful impact on people’s lives. Certainly, it may have facilitated better efficiency and streamlined processes that were drudgery otherwise; but I couldn’t find a place where it genuinely improved people’s lives. Nevertheless, from a technical perspective, I took much delight in designing and building solutions that achieved whatever the circumstances necessitated. I’m constantly humbled as I explore the ingenious ideas which perpetuate the decentralisation community in the hopes of creating more resilient societies.

Digital revolutions and the rise of the big networks

A close and careful study of the digital revolution reveals a fundamental shift in how societies cooperate and the formation of a global village governed by complex networks that empower individuals as the flow of information is maximised. Widely adopted technologies reached that state by allowing large networks of humans to exchange ideas in a digital marketplace where the cost of replicating ideas is negligible or zero. This revolution has been characterised by acceleration of change. It’s not just that things changed, but also that the time between each leap forward shortened. Technologists have continuously opted for pragmatic solutions which resulted in technologies that are rarely perfect, yet extremely powerful. This happened in a similar fashion to the evolution of life, wherein mutations solve adaptation problems while introducing others.

One such result of the fast-paced change is the centralised nature of most digital networks which are operated by very few companies. I refer to digital networks as digital systems that connect humans.

Protocols are like Lego

The Internet consists of several fundamental building blocks also known as protocols, that allow users to find each other and exchange information. A protocol is like a formal language definition that computers use to communicate with each other. Before describing the nature of these protocols, it’s worth taking a glimpse at the motivations of their designers. The Internet’s creators wanted the Internet to be ubiquitous and for everyone. This is evident in the writings of one of the fathers of the Internet, Vint Cerf. In a 2002 RFC (request for comment) titled “The Internet is for everyone”, Cerf professes this egalitarian ideology and lays out some of the hurdles that may be faced in the pursuit of that endeavor.

These fundamental Internet protocols facilitate most Internet activity, from browsing the Internet to sending emails, and all the way to writing and publishing this essay. For example, I used Google Docs to write this essay. To begin this act, I typed docs.google.com into the browser which then used the DNS (domain name system) protocol to request the digital address of Google Doc’s service. With the digital address at hand, known as an IP address, the browser was able to establish a connection to a remote computer (referred to as a server in this case) operated by Google. Once a connection has been established, both my computer and Google’s server became aware of each other’s IP address, thereby allowing the two computers to freely and reliably exchange information.

The exchange of information is made possible with TCP, Transfer Control Protocol, and IP, Internet protocol. TCP breaks the data exchanged into little packets (individual units of data ready for shipping), ensuring their successful delivery and verifying their integrity when repackaged.

IP is a protocol to make computers digitally addressable. In the case of Google Docs, I provide my username and password, and once it arrives at the Google server, it is checked, and if valid, Google will send back the list of my documents.

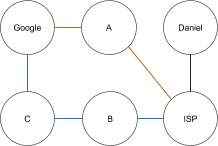

It may appear as if the example above involves only two participants, however that was intentional in order to simplify the procedure. In reality, every interaction between two parties relies on many more computers in the network to relay the packets between Google and me. It’s also important to note that there can be many possible paths between Google and me, so it looks more like this:

The power of the TCP protocol is that it creates a virtual direct link between two participants.

The graph above draws upon an academic area of study in mathematics known as graph theory. In graph theory there are two important fundamental units, namely vertices and edges. Edges are the lines that connect the vertices, which are represented by circles. In the graph above the vertices are computers and the edges are the connections between them. While seemingly abstract and simple, graph theory is used to model many types of relations and processes in different types of systems, such as digital and social systems.

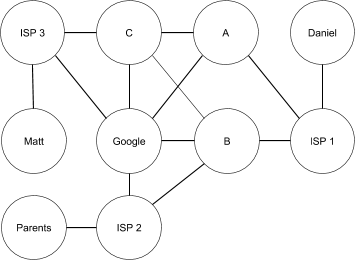

In a graph, measures of centrality and node influence can be used to identify the most important edges and vertices. These measures can tell us how important an edge or a vertex is to the graph. The most obvious important edge we’re all familiar with as Internet users is the one between our computer or smartphone and the ISP or mobile network operator. It’s enough to cut that link and your ability to communicate with the rest of the graph is lost. That constitutes a low degree of centrality of the edge (the connection). Conversely, when the idea is extended to Google, a high degree of centrality is to be measured due to the many edges that connect to it. This is illustrated in the following graph that represents a real world network of friends and family.

In this case, Google has the highest degree of centrality. Daniel’s ability to communicate with his friend Matt and parents depends on how they communicate. If much of this communication flows through Google, with the help of Gmail or Hangouts, the removal of Google will impede Daniel’s ability to communicate.

In other words, as we rely more and more on large corporations to operate networks that facilitate communication and idea exchange — arguably basic human rights — we stand the constant risk of being susceptible to these corporations’ dictates. The byproducts of this are: monopolies, concentrated decision making about what content is allowed (censorship), and the ability of governments to regulate free access to information with censorship.

This also raises the question of whether some of these companies are “too big to fail”; a phrase used to describe corporations that are so large and so interconnected that their failure would be disastrous to the greater economic system. If Google stopped working, what repercussions could it have on society?

The challenges with centralisation

The public discourse around net neutrality is directly related to the centrality of some internet companies. Net neutrality is the principle that ISPs should treat all data equally. Which begs the question, why wouldn’t they? An ISP may throttle or block access to certain services as a means of unfair competition: this happened when AT&T limited access to Facetime so as to upsell customers to more expensive data plans.

Moreover, the root of many of those problems lie in the incentive structures that sustain such corporations, namely ad-driven companies. For example, in the case of Facebook, there’s a constantly negotiated dynamic between Facebook users, the company, advertisers, and regulatory bodies. Because Facebook is free, it has to finance its operation by selling you, or rather your data, as a product to advertisers. The data collected is so revealing that they’ve introduced systems to predict the onset of depressive episodes and suicidal thoughts among users.

Even though the intentions behind this may be pure, once these systems reach high accuracy, it almost becomes inevitable to target users with relevant ads.

This problem has been recognised by Mark Zuckerberg in a post about his personal challenge for the year 2018: “With the rise of a small number of big tech companies — and governments using technology to watch their citizens — many people now believe technology only centralizes power rather than decentralizes it.” The recognition is an important step, however, I’m skeptical as to how he plans to tackle this.

Lastly, it’s hard to not mention China’s social credit system, which aims to give every citizen a score, effectively placing them on a scale of obedience. Technically speaking, it works by connecting payment systems, with government databases and the public transport system into a centralised system which tracks every move of every citizen, and can limit access to trains, flights, hotels, schools for their children, and jobs to those given a low score. Worst of all, it’s built in a way that alienates low-scorers in the form of blacklists. These disincentives are extremely effective in limiting basic human rights and don’t create much space for the citizens to participate in the shaping of the rules.

What becomes obvious is that the line between governments and corporations becomes finer as they both create a structure of norms and behaviours and wield their power to meet certain goals, many of which are not always in the interests of the individuals.

The alternatives

This all seems bleak, however it’s worth noting that the Internet protocols do not inherently favour such centralisation. Moreover, the specification of these protocols is not patented, which allows anyone to use them, implement them, and improve them. The protocols are like a language; a cultural artefact that remains alive and evolves as long as it’s spoken. The Internet cannot be easily shut down because it is decentralised. There’s no main Internet switch that is guarded 24/7, nor is there a single Internet headquarters office. Just the idea of it seems preposterous.

Much of the optimism in the decentralisation community comes from new networks and protocols that aim to complement the aforementioned ones with a strong focus on decentralisation. Some of the new fat protocols, as they’re often referred to, promise to dilute the concentration of decision making and to create a level playing field for all participants. Anyone with Internet access can participate, making them egalitarian by nature. It is very difficult to censor or block access, because control of networks is distributed to the network. While there’s no strict definition to decentralised networks, they rely on a technological architecture known as P2P, or Peer-to-Peer, which was popularised with Napster in 1999, BitTorrent in 2001, and more recently, Bitcoin in 2009.

These technologies provide a basis for large scale collaboration. They do so with the disintermediation of parties usually backed by a state government we’ve grown to rely on. Because the technologies facilitate global operation through the Internet, the entry burdens are lower than traditional banks, media outlets, and courts. For example, if you want to open a bank account in Germany you need an Anmeldebestätigung (town hall registration) for which you need to have a place to live in Germany. But if you want to open a digital wallet for cryptocurrencies, you just need a smartphone or computer.

However, these networks are very nascent and we’re only at the beginning of the journey. The history of these technologies and the big challenges they pose will clarify how they might influence the economic systems in the years to come.

Decentralisation is not easy

Decentralised networks pose many engineering challenges, making them principally inefficient in contrast to more efficient centralised networks. Decentralised networks often do away with the client and server model, e.g. the viewer and Netflix, respectively. Instead, every network participant bears some of the work of the server while being served by other participants.

This is exemplified in BitTorrent: when one downloads a movie, he leeches (downloading in BitTorrent jargon) from other seeders and becomes a seeder once he successfully downloaded chunks of the movie. Because leeching a movie requires establishing a connection to seeders (network participants with chunks of a movie), checking the integrity of the chunk, and then combining the different chunks to a watchable movie is a lot of work. By analogy, it’s like getting a section of a film from many different movie rentals, making sure you’re not missing any sections and then combining them to form a movie. It’s more efficient to just rent the full movie.

These inefficiencies have contributed to the rise of centralised streaming services which provide a smoother experience. This is indicated by Internet usage statistics. In November 2004, BitTorrent was responsible for 25% of all Internet traffic. As of February 2013, BitTorrent was responsible for 3.35% of all worldwide bandwidth. Netflix and Youtube account for over 50% of Internet traffic in North America during peak hours as of 2018.

It’s important to note that the statistics differ depending on the source and percentages don’t denote the aggregate volume. So perhaps it was traffic growth that shifted the distribution without BitTorrent’s volume decreasing. I’d argue for two reasons when discussing BitTorrent’s relative decline, namely BitTorrent’s inefficiency and the lack of an incentive structure that rewards content creators.

In the case of BitTorrent for content sharing, it has been clearly outperformed by centralised alternatives. Because BitTorrent’s main use case was content piracy, legally sound alternatives with better user experiences, e.g. Netflix, won the masses over. One of the obvious downsides with BitTorrent was the lack of an incentive structure. Content seeders have no reward which increases the reliance on good will. Additionally, the protocol is optimized for the dissemination of content absent any recognition of its creators.

Satoshi Nakamoto, Bitcoin’s anonymous creator, understood that very well and introduced a simple incentive structure to participants of the network as part of the Bitcoin protocol.

The protocol is the formal definition of the communication language between all computers running the Bitcoin software. An incentive is a payment or reward used to stimulate greater output or investment. Without knowing much about Bitcoin, the idea is that you can invest in running mining software and be rewarded. The mining software consumes computational resources and electricity (the investment) and the chances of winning the reward correlates to the computational power applied. In Bitcoin jargon, this is known as proof of work. This happens in the form of a race every ten minutes to “mine” the next block of the blockchain, the ledger which stores the ownership of the virtual tokens. The reward for winning the race is newly minted Bitcoins. As long as the network has miners, Bitcoin holders can transact these virtual tokens. The virtual tokens are a store of value and its price is determined by markets and the negative externalities (electricity) incurred by its miners.

But why would anyone want virtual tokens?

Network Effects

As more miners invested electricity in mining and the ability to quasi-anonymously transact Bitcoins became possible, the Bitcoin network grew, as did the value of Bitcoins. This is described as network effect:

“Network effects are mechanisms in a product and business where every new user makes the product/service/experience more valuable to every other user.” (NFX)

The Bitcoin network is able to process approximately ten transactions a second without a central bank. What’s truly historic about Bitcoin is that it is both the first digital and first decentralised currency.

Besides being digital and decentralised, Bitcoin is inferior in almost every other regard. This explains much of its current usage: illicit drug trading, money laundering, crime, and speculation. The lack of a central authority means that users are no longer protected by an operator who can compensate or correct when technical errors arise. The news is filled with stories about user’s irrecoverable lost Bitcoins. Prices tend to fluctuate dramatically. The ten transactions per second limitation barely suffices for a cafe chain, let alone a global economy. Moreover, actually using Bitcoins for personal or commercial activity is overly complex. One needs to register to an exchange, verify identity, look at perplexing graphs, make a bid, wait for confirmation, pick a digital wallet from the many available, and then make sure you have a backup.

To make it just a little more confusing, disagreements within the developer communities behind these protocol result in forks. These forks can result in Bitcoin holders suddenly owning more than a single currency, as happened with Bitcoin Cash. This is all very confusing. For most legitimate use-cases it’s not worth the trouble. But it may not stay like that forever.

This may be reminiscent of the Internet in the late 90s when the zeitgeist was to expatiate about how the Internet is the next big thing. In actuality, putting aside all promise and obvious progress it brought, it was slow, clunky, loud (remember the modem dial up sound), complicated, and aesthetically subpar.

Generally when a discrepancy between reality and promise as such emerges, financial opportunities in the form of speculation instruments arise. In the late 90s it eventuated with the dot-com bubble exploding. In the years following the dot-com bubble, waves of companies shut down. But some companies survived. Companies who lived up to the promise and were able to create sustainable financial models around their value offering. Graphic design software vendor Adobe Systems (ADBE) peaked at 43.66 USD in November 2000. It surpassed that high in March 2007, and at the time of writing, it’s trading at a proud 243.63 USD. A shallow analysis of the crypto-currency boom of late 2017 when Bitcoin hit 20k USD has remarkable similarities, especially inflated prices driven by the promise and hope of new technology.

What if many of decentralisation technologies are just at their beginning? What could happen when their upsides outweigh the weaknesses of current centralised equivalents? While that’s a very difficult question to answer, a closer examination of centralised equivalents can shed much light on how this might play out.

Scalability

If you live in a developed country with a modern economic system, there’s a good chance you have multiple paper-thin plastic cards with a little chip on you at most times. It allows you to purchase goods and services everywhere in the world. In fact, you often don’t need the card at all. You step out of a car and the the systems behind the scenes ensure your driver is paid from your bank account. You can reliably check your balance at anytime, and when fraud is detected, fraudulent transactions are quickly reversed. Additionally, if you aren’t utilising the credit-line allocated, its either free or almost free. The Visa network can evidently process thousands of transactions per second. There is scarcely any downtime, much like the reliable electricity grid we’ve grown accustomed to in the developed world. Currently, most decentralised networks have not reached that level of scale. So scalability is one of the utmost technical challenges to be solved.

There are several different scalability solutions that are being explored. Much of the difference when comparing the solutions systematically lies in the balance they each strike between the level of trust, decentralisation, simplicity and difficulty of implementation, as well as efficiency gains. The four main avenues of thought are:

- Storage improvements — more compact storage formats for blockchain data

- State channels — which represents an off-chain alteration of state, secured by eventual settlement in a blockchain.

- Sharding — A shard is a horizontal portion of a database (in this case a Blockchain), with each shard stored in a separate server instance. This spreads the load and makes the Blockchain more efficient because the server instance will have only a part of the data on the blockchain.

- Proof Of Stake — A way to reduce negative externalities (computation/electricity) by introducing a different consensus mechanism.

The point here is that all of these solutions need time to develop and mature. A lot of money is flowing from both VCs and ICOs allowing a new class of company to innovate and drive this technological shift forward. What’s more, these companies’ incentives are structured so as to maximize decentralisation and create networks that better align the network participant’s incentives with each other.

The role of regulatory bodies in such rapid economic shifts tends to be instrumental to the way they pan out. The SEC and many other important regulatory bodies have launched their own research projects and they seem to be open to allow innovation. Regulations will have to be shaped in such a way that protects citizens from fraudulent ICOs and unsavory businesses while allowing innovation to continue.

Lastly, and this may be the biggest hurdle to mainstream adoption, is ease of use. Blockchain and cryptography-based decentralised protocols are inherently complex. Because there’s no single authority behind it, much responsibility is placed on the user. Given that the populations who’d probably benefit from this the most are the developing world, we’re faced with the challenge of making it accessible. Good user experience abstracts away the details users need not worry about. Presently, setting up a digital wallet is complicated, and there’s too much choice. The risk of theft is high for novice and advanced users alike, and theft is often irreversible due to the lack of central authority. What should real world transactions look like?

In summary, the problems of centralised networks are slowly becoming a public concern. The key weaknesses are their tendency to create monopolies and to oppress freedom. The materialisation of ideas in the decentralisation movement will give rise to better protocols and technologies that place freedom of expression and healthy collaboration as a priority. Novel incentive structures will maximise the networks participants’ interests. Regulation will serve an important role in legitimising new commercial activity and innovation. We may even see a shift in the focus of the net giants from ad-driven growth to more intricate and diverse financial models. Besides the technical challenges, a new space of jobs and skills will emerge. Civil liberties can be better protected with the right tools, and decentralisation promises to be at the forefront of this cause.